The Samaritan Woman at the Well: John 4.7 – 30

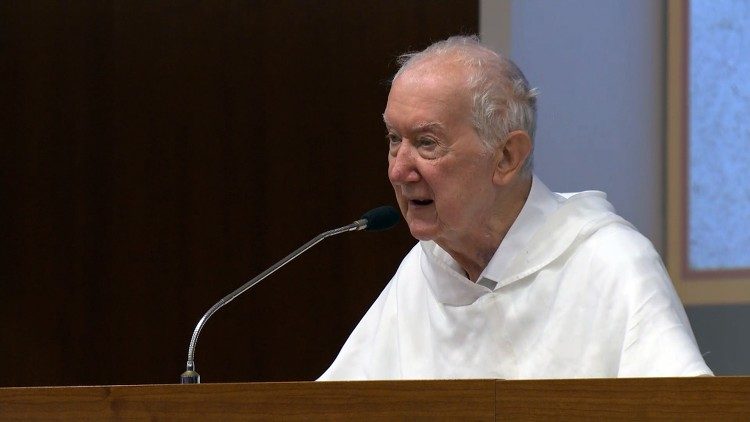

Spiritual Input – October 9th

Fr. Timothy Radcliffe OP

Today we begin to reflect on B.1 of the Instrumentum Laboris, ‘A Communion that radiates.’ The theme that emerged most frequently in our sessions last week was formation. So how can we all be formed for communion that overflows into mission?

In John Chapter 4, we hear of the encounter of Jesus with the woman at the well. At the beginning of the chapter she is alone, a solitary figure. By the end, she is transformed into the first preacher of the gospel, just as the first preacher of the resurrection will be another woman, Mary Magdalene, the Apostle of the Apostles: two women who launch the preaching first of the good news that God has come to us, and then the resurrection.

How does Jesus overcome her isolation? The encounter opens with a few short words, only three in Greek: ‘Give me a drink.’ Jesus is thirsty and for more than water. The whole of John’s gospel is structured around Jesus’ thirst. His first sign was offering wine for the thirsty guests at the wedding in Cana. Almost his last words on the cross are ‘I am thirsty’. Then he says, ‘It is fulfilled’ and dies.

God appears among us as one who is thirsty, above all for each of us. My student master, Geoffrey Preston OP, wrote, ‘Salvation is about God longing for us and being racked with thirst for us; God wanting us so much more than we can ever want him.[1]’ The fourteenth century English mystic, Julian of Norwich said, ‘the longing and spiritual [ghostly] thirst of Christ lasts and shall last till Doomsday.[2]’

God thirsted for this fallen woman so much that he became human. He shared with her what is most precious, the divine name: ‘I AM is the one speaking to you.’ It is as if the Incarnation happened just for her. She learns to become thirsty too. First of all for water, so that she need not come to the well every day. Then she discovers a deeper thirst. Until now she has gone from man to man. Now she discovers the one for whom she had always been longing without knowing it. As Romano the Melodist said, often people’s erratic sex life is a fumbling after their deepest thirst, for God[3]. Our sins, our failures, are usually mistaken attempts to find what we most desire. But the Lord is waiting patiently for us by our wells, inviting us to thirst for more.

So formation for ‘a communion which radiates’, is learning to thirst and hunger ever more deeply. We begin with our ordinary desires. When I was ill with cancer in hospital, I was not allowed to drink anything for about three weeks. I was filled with raging thirst. Nothing ever tasted so good as that first glass of water, even better than a glass of whisky! But slowly I discovered that there was a deeper thirst: ‘Oh God, you are my God for you I long, like a dry weary land without water.’ (Psalm 62).

What isolates us all is being trapped in small desires, little satisfactions, such as beating our opponents or having status, wearing a special hat! According to the oral tradition, when Thomas Aquinas was asked by his sister Theodora how to become a saint, he replied with one word: Velle! Want it[4]! Constantly Jesus asks the people who come to him: ‘Want do you want?’; ‘What can I do for you?’ The Lord wants to give us the fullness of love. Do we want it?

So out formation for synodality means learning to become passionate people, filled with deep desire. Pedro Arrupe, the marvellous superior general of the Jesuits, wrote: ‘Nothing is more practical than finding God, that is, than falling in love in a quite absolute, final way. What you are in love with, what seizes your imagination, will affect everything. It will decide what will get you out of bed in the morning, what you do with your evenings, how you spend your weekends, what you read, who you know, what breaks your heart, and what amazes you with joy and gratitude. Fall in love, stay in love, and it will decide everything.[5]’ That passionate man, St Augustine, exclaimed: ‘I tasted you and now hunger and thirst for you; you touched me, and I have burned for your peace[6]’.

But how do we become passionate people – passionate for the gospel, filled with love for each other – without disaster? This is fundamental question for our formation, especially for our seminarians. Jesus’ love for this nameless woman sets her free. She becomes the first preacher but we never hear of her again. A synodal Church will one in which we are formed for unpossessive love: a love that neither flees the other person nor takes possession of them; a love that is neither abusive nor cold.

First it is an intensely personal encounter between two people. Jesus meets her as she truly is. ‘You are right in saying “I have no husband”. For you have had five husbands and the one you have now is not your husband. What you have said is true.’ She gets heated in response and replies mockingly: ‘Ah, so you are a prophet’.

We should be formed for deeply personal encounters with each other, in which we transcend easy labels. Love is personal and hatred is abstract. I quote again from Graham Greene’s novel The Power and the Glory, ‘Hate was just a failure of imagination.’ St Paul’s very personal disagreement with St Peter was hard but truly an encounter. The Holy See is founded on this passionate, angry but real encounter. The people whom St. Paul could not abide were the underhand spies, who gossiped and worked secretly, whispering in the corridors, hiding who they were with deceitful smiles. Open disagreement was not the problem.

So many people feel excluded or marginalised in our Church because we have slapped abstract labels on them: divorced and remarried, gay people, polygamous people, refugees, Africans, Jesuits! A friend said to me the other day: ‘I hate labels. I hate people being put in boxes. I cannot abide these conservatives.’ But if you really meet someone, you may become angry, but hatred cannot be sustained in a truly personal encounter. If you glimpse their humanity, you will see the one who creates them and sustain them in being whose name is I AM.

The foundation of our loving but unpossessive encounter with each other is surely our encounter with the Lord, each at our own well, with our failures and weakness and desires. He knows us as we are and sets us free to encounter each other with a love that liberates and does not control. In the silence of prayer, we are liberated.

She meets the one who knows her totally. This impels her on her mission. ‘Come and see the man who told me everything that I have ever done.’ Until now she has lived in shame and concealment, fearing the judgment of her fellow citizens. She goes to the well in the midday heat when no one else will be there. But now the Lord has shone the light on all that she is and loves her. After the Fall, Adam and Eve hide from the sight of God, ashamed. Now she steps into the light. Formation for synodality peels away our disguises and our masks, so that we step into the light. May this happen in our circuli minori!

Then we shall be able to mediate God’s unpossessive pleasure in every one of us, in which there is no shame. I shall never forget an AIDS clinic called Mashambanzou on the edge of Harare, Zimbabwe. The word literally means ‘the time when elephants wash’, which is the dawn. Then they go down to the river to splash around, squirt water over themselves and each other. It is a time of joy and play. Most of the patients were teenagers who did not have long to live but it is a place of joy. I especially remember one young lad called Courage, who filled the place with laughter.

In Phnom Penh, Cambodia, I visited another AIDS hospice run by a priest called Jim. He and his helpers collect people who are dying of Aids in the streets and bring them back to this simple wooden hut. One young man had just been brought in. He was emaciated and did not look as if he had long to live. They were washing and cutting his hair. His face was blissful. This is God’s child in whom the Father delights.

The disciples return with food. They are shocked to see Jesus talking to this fallen woman. Wells are places of romantic encounter in the Bible! As with her, the conversation has a slow beginning. Two words only: ‘Rabbi, eat.’ But she has become a preacher even before them. Our role as priests is often to support those who have already begun to reap the harvest before we even wake up.

[1] Hallowing the Time:Meditations on the Cycle of the Christian Liturgy, Darton, Longman and Todd, London, 1980, p.83.

[2] Revelations of Divine Love, chapter 31

[3] Cant. 10, quoted by Simon Tugwell OP, Reflections on the Beatitudes, Darton, Longman and Todd, London, 1980, p.101

[4] Placid Conway OP, St Thomas Aquinas, Longmans Green, London 1911, p.88

[5] Virgil Elizondo Charity New York 2008 p.22

[6] Breviary Reading for the Feast: Confessions, Bk 10, xxvii (38).